The Delightfully Surprising Enjoyment of Aged Inexpensive Everyday Wines

All over the Internet, you will come upon such statements as these:

“Something like 98% of wine is drunk within 48 hours of purchase and is meant to be consumed young.”

“As much as 90 percent of the wine bought in the U.S. is drunk within 24 hours.”

“The vast majority of wine in America — estimates range from 70% to 90% — is consumed within 24 hours of purchase.”

“In general bottles under £7, especially whites and rosés, are not worth hanging on to for more than a couple of months. Most wines these days are designed for immediate consumption.”—Fiona Beckett, a fine wine writer, who most likely did immediately consume such bottles as appear in this article and so didn’t allow herself the chance to make the discovery I made and now you will be encouraged to make.

As much as these statements may differ slightly, they are inarguable. They tell us when these wines are drunk. They don’t tell us when these wines should be drunk for maximum enjoyment.

What I’m here to tell you is that, with a few exceptions, almost every wine you buy will get better with time.

Sometimes a lot better, sometimes with a lot of time.

And even more the contrary view: almost every one of them will get better after they’ve been opened, sometimes for days, sometimes, but rarely, for weeks, in one case herein reported, for months.

The one inalterable rule: these wines must, whether red or white, be stored, once opened and however much consumed, in the refrigerator. You don’t need a device (particularly one that pumps out air from the bottle; it pumps out the essence of the wine as well). Just the cork, any cork that fits, will do.

An aside: most white wines are drunk too cold. Most red wines are drunk too warm. Red wines, unopened or opened, stored in the refrigerator should be brought out to warm up to, ideally, between 55°F and 65°. If you don’t have a wine thermometer (I don’t), use your tongue.

All the wines I’ll mention here are from my wine cellar.

Most of them are old, because this piece is about the aging of what are mostly inexpensive, supposedly simple wines, those that generally “are consumed within 24 hours of purchase,” whereas most of mine, reported upon here, have been consumed after years since purchase.

Many of them might be described as “odd,” which is to say rare, in the sense of uncommon.

I own plenty of what I’d call rare, rare wines, mostly high-end red wines from the best vintages of the 1970s and 1980s, and most of those French, Italian, and Spanish. The 1970 Barolos, red Bordeaux, and red Riojas, for example, are now fifty-five years old. When will I drink them? As soon as I am with people with whom to share them and who know that this is a rare (no pun) opportunity. (And always with food, though they should be tasted first.)

Like most people, what I drink every day (lunch and dinner) are wines like those in this piece, so-called everyday wines, as “odd” as some of mine may be.

As I said, almost every one of these wines is old. Otherwise, this article would not exist. Its basic point is that almost all wines, no matter their age, get better sometime after they have been opened.

I have insufficient space to say much about any of these many wines. Please use your search engine of choice to do your own research.

Had I space, I might, for some of these, have written as I did in my Cook’s Cook Odd Bottle feature about a bottle headlined, Old, Cheap, Astounding, one of the finest bottles of wine I’ve ever drunk, regardless of age or price (or renown). If you would like to read about it, you will see that it still carries its $4.99 price tag from when it was purchased in 1985. It’s a wine produced in such numbers that you can buy a recent vintage of it today almost anywhere, and from some merchants for less (its price adjusted for inflation, as will be all new prices I quote) than I paid 40 years ago.

Otherwise, here are some common and some unusual (odd) wines that gave themselves up for this experiment/experience, conceived after I had drunk, daily for three days, an open red wine that then went back into the refrigerator and was not seen again for three-and-a-half months.

“What will this be like now?” I wondered.

I’ll tell you later. (But you can probably guess.)

To eliminate some wines to which this “rule” (okay, I don’t make rules, only offer suggestions):

Rosés. Yes, some can be aged, but those are uncommon, and even those offer the great burst of fresh and non-enduring (but who cares?) enjoyment when young.

Beaujolais nouveau. Chill and drink it, if you must. Better to spend a bit (or a lot) more money on one of the ten Beaujolais crus or even a simple Beaujolais. We recently opened a 20+-year-old Beaujolais Village, and it was just fine. But it did not, unlike many of the wines below, improve with post cork-pulled time.

Sparkling wines of any kind, from modest Spanish Cavas to some very good Australian sparkling rosés to the greatest Champagnes. They do not improve with time after having been opened, even when their fruit comes further forth, because every one of them will lose carbonation, and that’s too big a loss to compensate for a liberation of fruit upon the tongue.

I have insufficient space to say much about any of these many wines. Please use your search engine of choice to do your own research.

Had I space, I might, for some of these, have written as I did in my Cook’s Cook Odd Bottle feature about a bottle headlined, Old, Cheap, Astounding, one of the finest bottles of wine I’ve ever drunk, regardless of age or price (or renown). If you would like to read about it, you will see that it still carries its $4.99 price tag from when it was purchased in 1985. It’s a wine produced in such numbers that you can buy a recent vintage of it today almost anywhere, and from some merchants for less (its price adjusted for inflation, as will be all new prices I quote) than I paid 40 years ago.

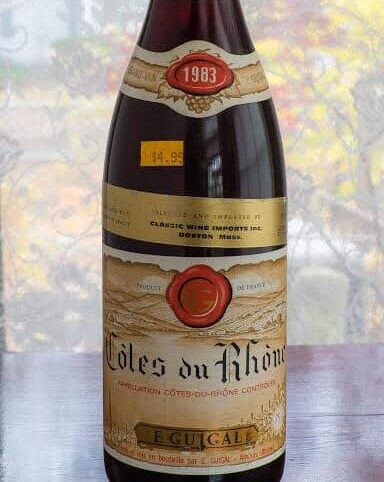

1983 Guigal Cotes du Rhone