For hundreds and thousands of years a circle of fire, a hearth in various forms, has provided the principal focal point of a human home. Whether a small slow-burning pyre, or a circle of stones in which a fire is built, or a metal brazier made out of repurposed drums called an mbaula, here in Zambia’s upper Zambezi Valley fire is still the focus of a family home. While researching the history of the hearth, I was surprised to learn the derivation of the word ‘focus’ (n.): 1640s, “point of convergence,” from Latin focus “hearth, fireplace” (also, figuratively, “home, family”), which is of unknown origin. Used in post-classical times for “fire” itself.

When I first arrived to live with Chris (a farmer who would later become my husband) and began to cook in his makeshift open-air kitchen under the crown of a massive mongongo tree, he had a diminutive gas stove in which the oven shelf collapsed under the weight of a leg of lamb. A wood fire built in an mbaula was often a more practical way of roasting or grilling meat and vegetables, while in the winter in our house in which there are few walls and doors, it was also an indispensable foot warmer when placed under our dining room table during dinner.

Today, I have access to an mbaula and a wood-fired oven. Our farm workshop—the beating heart of our commercial farm where aging equipment is kept running; where mechanics, welders, carpenters and builders create and improvise—constructed the wood-fired oven for me on one side of a donkey boiler. Built atop a circle of fire, a donkey boiler is an enclosed drum in which water running in and out is heated for our kitchen and bathrooms.

For the Zambian women working or training in my kitchen, cooking on a circle of fire is a skill they learned as young girls observing their elders. House cleaning and cooking are largely familial internships starting around eight-years-old, passed from mother to daughter, generation to generation. While cooking in the traditional home is seen as women’s work, in Zambian restaurant kitchens it is a domain mostly dominated by men. Here, I now only employ women in my chef training program. Not only is their know-how of cooking on fire invaluable, their experience with using traditional indigenous ingredients is innate. This allows for my bush gourmet recipes to be adapted by cooks in nearby villages, or in turn, by chefs in surrounding lodge and hotel restaurants.

Together we combine modern European cooking techniques with traditional African cooking techniques, such as the use of fire. By collaborating this way, I hope to not only contemporize traditional ingredients, but to also enhance their age-old culinary traditions that foster connection to the ground on which they live and eat. Fire is fundamental to traditional food preparation and preservation. Along with grilling and roasting, Zambian women use fire to extract oil from wild mongongo nuts. They do this by pounding and boiling the fatty nuts in water over the hearth until oil starts to rise to the top. They then skim this off and use the oil for cooking and flavoring their dishes.

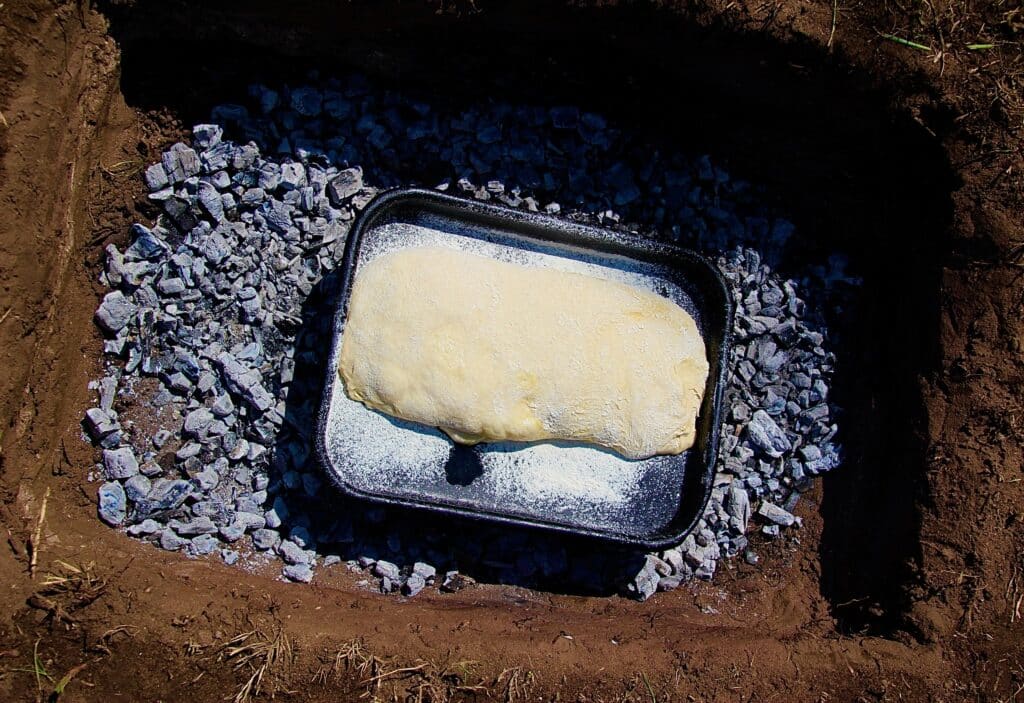

Fish and meats are preserved by smoke-drying. Hung above smouldering open-air fires, shelf-life, texture and flavor are added to these proteins. In our wood-fired oven we mostly roast meats and vegetables, as well as the garden and wild ingredients we use to flavor our salsas and sauces. I make a pâté with bream that is smoked in mopane, one of the hardest woods found in our riverine forests alongside the Zambezi River. I also make ciabatta bread in a wood-fired oven dug into the depths of the Kalahari sand around our house. Using dried, hard wood foraged from the woodland in which we live, a fire is lit in the hole. When the temperature is judged to be correct for baking, hot coals are removed and a tray with the ciabatta dough is balanced on two flat stones nestled in the remaining embers. The hole is covered with a galvanized iron sheet on which the burning coals that were removed are placed, and the oven is sealed by placing rocks on each corner.

One of the tastiest wood-fired breads I have eaten in Zambia is sipotohayi, a gluten-free cornmeal bread eaten by the Lozi people in western Zambia as a treat at teatime. Cooked between two metal discs over an mbaula, sometimes in banana leaves, it is mostly eaten with jam or peanut butter. When I worked as a chef consultant at a high-end safari lodge in Zambia’s South Luangwa, we centered high tea around using sipotohayi in place of scones. We offered both savory and sweet versions—some with flavored cream cheese and roasted sweet peppers, and others with jam and clotted cream. Both were a complete hit! ![]()

RECIPE: Sipotohayi